The Story of My Hummer

Written by Alan Wenbourne in March 2021

In May 1994 I took employment in the USA. As it was for a contract period we decided that my wife Lesley would join me in August for the period, and that it would be worth shipping over some of our furniture, rather than buying new or renting. In the process of arranging this, Lesley phoned me to ask if she should ship her sewing machine (planning ahead for the long, cold Michigan winter days and evenings) and if I could make it work from 110V mains power. I confirmed this as possible. Then she suggested that as there was plenty of space in the packing case, did I want my Meccano? To which I said no. As all good wives do (ignore their husbands that is), she had my Meccano shipped anyway.

In January of 1996 we visited the Auto Show at the Cobo Arena, downtown Detroit. There we came upon the AM General (AMG) stand exhibiting several Hummers. These were the civilian version of the US Army’s High Mobility Multipurpose Wheeled Vehicle (HMMWV), seen in figure 1, which became more widely known in the military as Humvee or Hummer.

![Figure 1: High Mobility Multipurpose Wheeled Vehicle [Photo: Michael Green, <em>Hummer: The Next Generation</em>]](/assets/articles/000095-the-story-of-my-hummer-figure-1-small.jpg)

Figure 1 High Mobility Multipurpose Wheeled Vehicle [Photo: Michael Green, Hummer: The Next Generation]

The military version had gained a reputation for service and reliability — it was reported that 2,500 Humvees went out on the Desert Storm campaign and 2,500 returned in working order (perhaps they had good spares back-up — my scepticism!) This reliability record, together with the vehicle’s impressive stature and performance, made them popular with celebrities who bought them, such as Arnold Schwarzenegger, and raised many requests of AMG to produce the civilian version introduced in 1992.

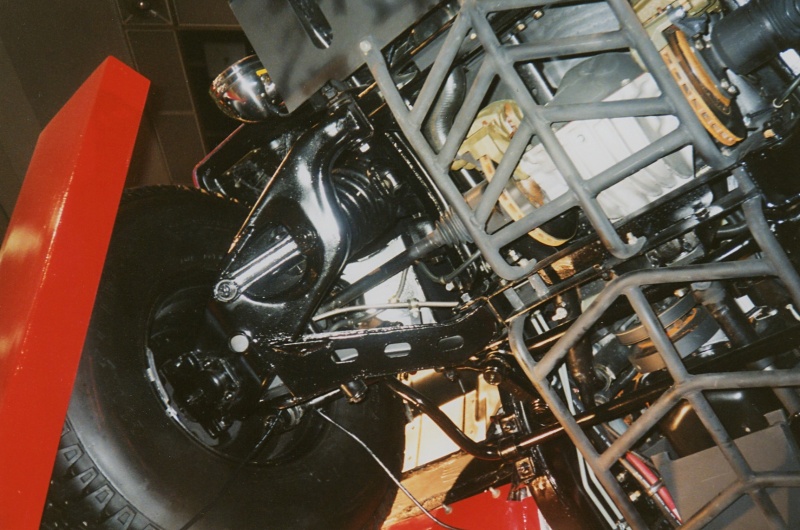

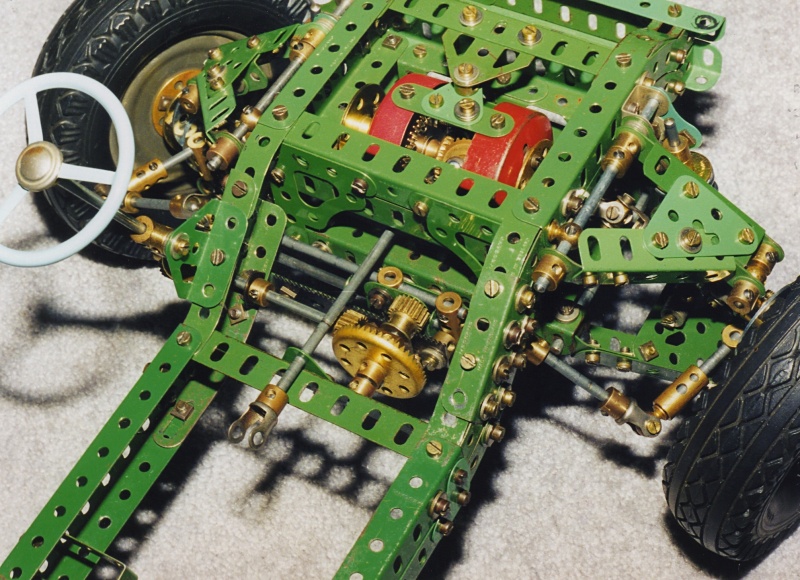

On the AMG stand was a Hummer ‘reared-up’ (figure 2), allowing us to stand underneath. In studying the drive train I realised the possibility of a long-standing wish to model a four-wheel drive, independently sprung vehicle chassis in Meccano, so here comes my return to the hobby after a 35-year absence — thanks to Lesley’s forethought! I picked up loads of literature and we headed for home.

Figure 2 Underneath a Hummer

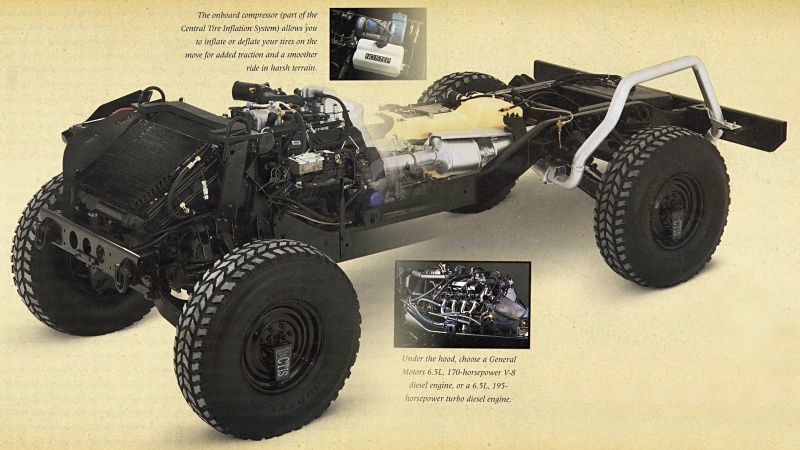

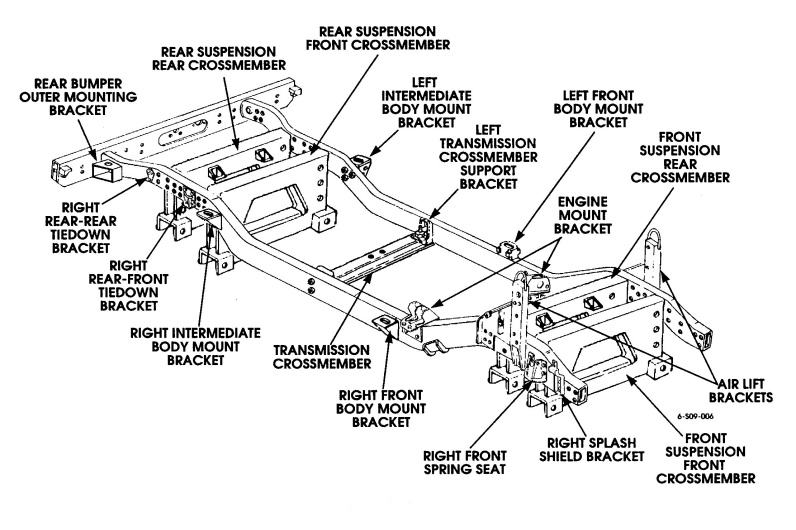

Starting on the chassis frame, as best I could from a picture in the Hummer brochure (figure 3), I soon discovered that I needed more detailed information, especially with respect to the frame sections that arched over the axles, suspension geometry and hub reduction drop gearing, which I was anxious to reproduce as authentically as possible to a scale of 1:6.

Figure 3 A page from the Hummer brochure

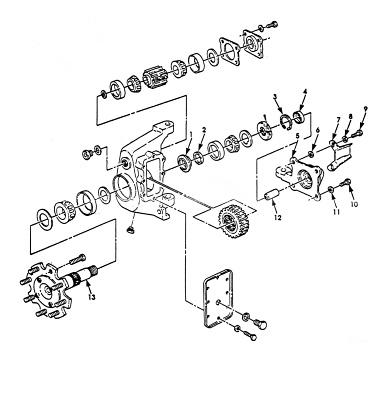

The search for more information led me to a local AMG dealer where, as seen in figure 4, I discovered Hummers galore! Here I befriended the service manager, explaining what I was doing and why I needed more information. To my delight he allowed me to browse the Hummer service manuals and photocopy the pages I needed (figures 5–7). This led to much more accurate modelling of the chassis, suspension and hub gearing.

Figure 4 Hummers lined up at the dealer

Figure 5 Service manual diagram

Figure 6 Service manual diagram

Figure 7 Service manual diagram

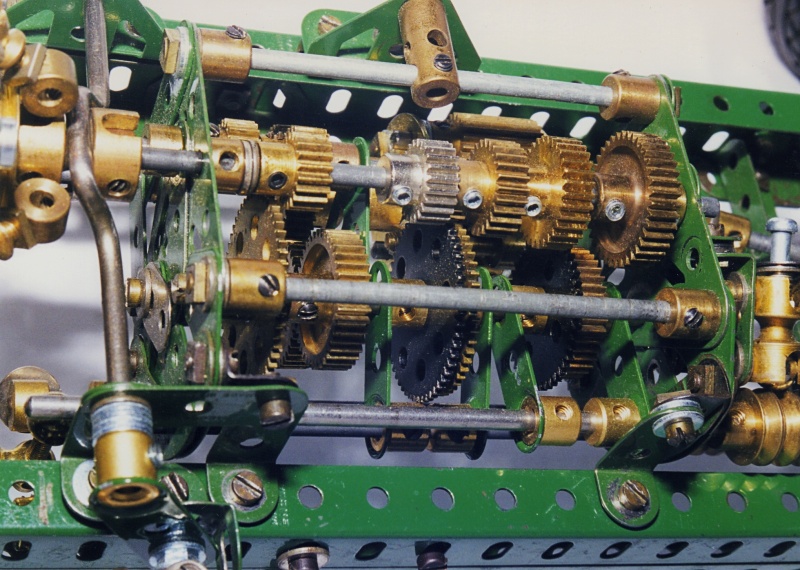

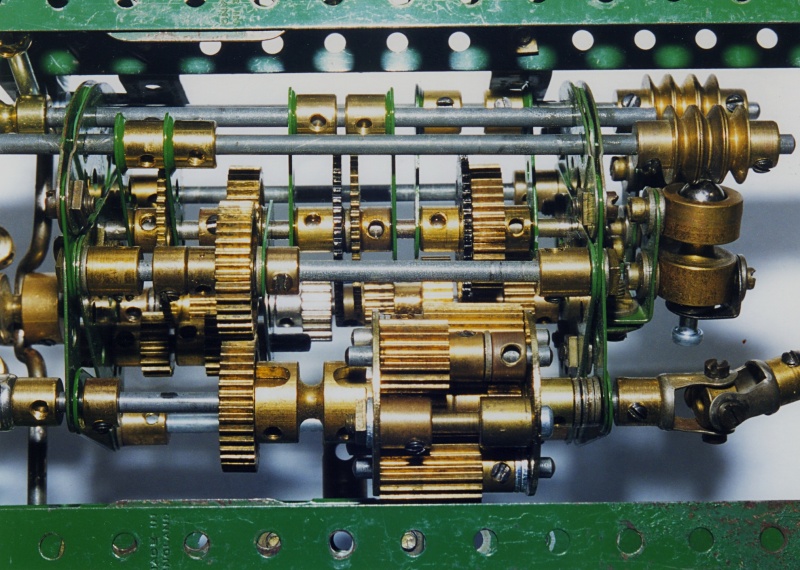

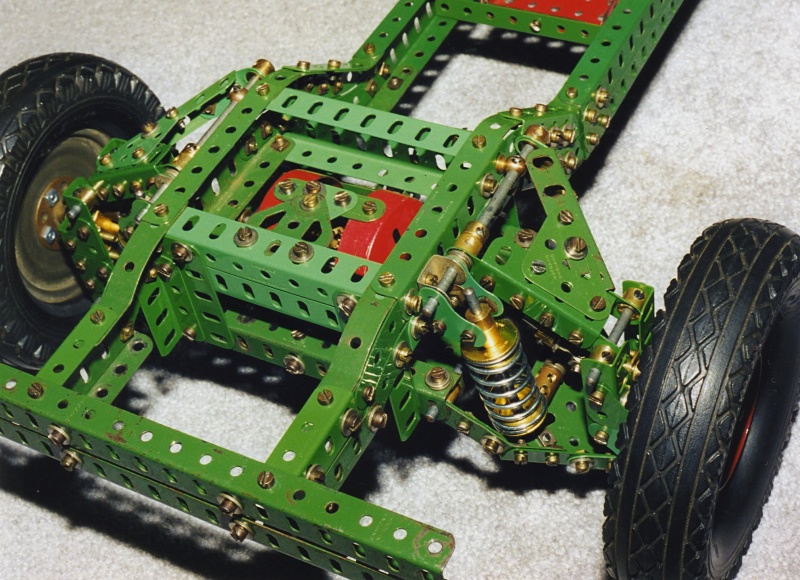

The 1:6 scale chassis went through several stages of development, being driven originally by an E20R motor through a 5-speed and reverse crash change gearbox based on keyed rods, with spur gear inter-axle differential and inboard bevel gear differentials at the front and rear axles (figures 8–11).

Figure 8 Gearbox

Figure 9 Gearbox

Figure 10 Rear differential

Figure 11 Rear suspension

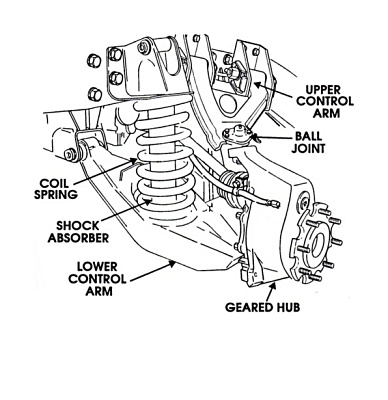

The independent suspension used non-Meccano coil springs in order to support the chassis weight and provide the degree of jounce (⅝”) that the scale required. All hubs were equipped with 1.92:1 reduction (25/13) drop gearing to reduce halfshaft torque and provide the necessary ground clearance. Steering was by rack and pinion with Ackerman geometry, as shown in figure 12.

Figure 12 Front suspension and steering

The wheels and ashtray tyres were Goodyear Eagle from my 1960 vintage model Grader (featured in the July 1960 issue of Meccano Magazine) as was the clutch designed for the same model (featured in the May 1960 issue of Meccano Magazine). The tyres were changed later to Goodyear Wrangler to match those of the production vehicle.

The prime mover was later changed to a 12V DC motor running off a 7.2V nickel-cadmium battery and speed controller to facilitate radio control. Apart from the freedom from an umbilical cable, this provided much better proportional speed control and remote steering.

In my aim for authenticity, it bugged me that the production Hummer was fitted with three Torsen T-1 (Type A) geared torque biasing limited slip differentials, but the model had open differentials. So another diversion into the research of and Meccano modelling of various types of differential became a protracted project, which resulted in the article A Clutch of Differentials (featured in the March 2000 issue of Constructor Quarterly). During this time I conceived an alternative design of Torsen-type differential, which would overcome some of the known manufacturing, assembly and set-up difficulties of the Torsen unit. Two Meccano models of this design were built using 12- and 14-tooth helical pinions.

Another protracted study of US and UK patent law and prior art revealed several other interesting limited slip differential designs/inventions, some of which were also modelled in Meccano. However, after reading dozens of patents, it appeared that my idea did not violate any prior art, so I proceeded to investigate patent protection.

The first thing I needed to do was to establish that my employer, Ricardo Inc. , would not lay claim to my invention. This was likely to be a problem because Ricardo design consultancy included many clients and projects associated with the automotive industry. They had taken over the FFD transmission business and had produced their own differential design! Several meetings ensued during which I stressed that I had not worked on any differential designs or projects and that my proposed invention was conceived entirely in the execution of my hobby.

Ricardo decided that it was most unlikely that they would get involved in the special worm/helical gearing of the type required of the invention, and gave me the assurance that I needed to proceed on my own.

Having determined that patent costs in the US are ten times that of the UK, I decided to pursue UK patent protection by drafting words and drawings. Then I discovered that US residents and aliens were not allowed to file for patent protection in foreign countries without US approval. Efforts in seeking this approval proved so difficult and frustrating that I gave up, knowing that I would be retiring back to the UK in a few years time and that it should be easier to file an application then. I retired and returned to the UK in 2003 but found no time to pursue the patent application. My IP remains protected in the two Meccano models stored in my collection! I suspect that there is little point in seeking patent cover of my ideas now that so many current differential and traction control systems are electro-hydraulic.

In August 2002 my visiting grandson and I visited the Woodward Dream Cruise event where thousands of classic and custom car enthusiasts come to Michigan to show their vehicles. It was here we came across this beautifully customised H1 Hummer, which I photographed, inside and out (figures 13 and 14). One could sit in the driving seat of one of these vehicles and just reach the shoulder of the front seat passenger with an outstretched arm! This was because half of its monster V8 engine occupied the cabin, which allowed a very low centre of gravity that contributed to the vehicle’s impressive off-road performance.

Figure 13 H1 Hummer

Figure 14 H1 Hummer interior

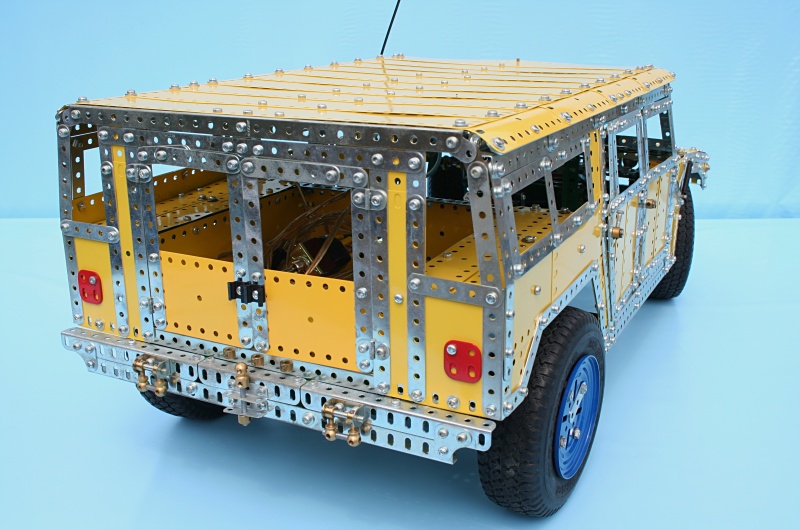

Whilst in the US, Lesley asked if I was going to model a body for the Hummer. I had not intended to, as the chassis was the main objective, but she can be persuasive, so I decided to consider a body.

The first thing was to decide on colour — I did not want to use red and green despite those colours being of my era, but having seen yellow Hummers around I considered that possibility despite having very few yellow parts.

My Meccano supplier at that time was Ray Zuehlke of Valley Transport Inc. in Arkansas. Ray posed the question: Liverpool or French yellow? So another trip to the Hummer dealer’s lot was made to try and match the best shade of yellow, where this beautiful yellow Hummer was on display (figure 15). This looked a lot like French yellow to me, so the planning for a body began.

Figure 15 Yellow hummer at the dealer

I had a 1:18 scale die-cast model Hummer with such excellent detail that I was able to scale this up to 1:6 and draw the side and front elevations on paper on the kitchen table. This would enable me to lay Meccano parts on it to match the shape requirements. The necessary parts were ordered, some from Ray (who was running down stocks to end his Meccano business) and from Geoff Wright who came to the rescue for the remainder. The resulting body, trimmed with zinc strips, is shown in figures 16 and 17 and features opening doors either side, double doors at the back, front hinged hood, sky lifting and crash bar attachments.

Figure 16 The completed model

Figure 17 The completed model

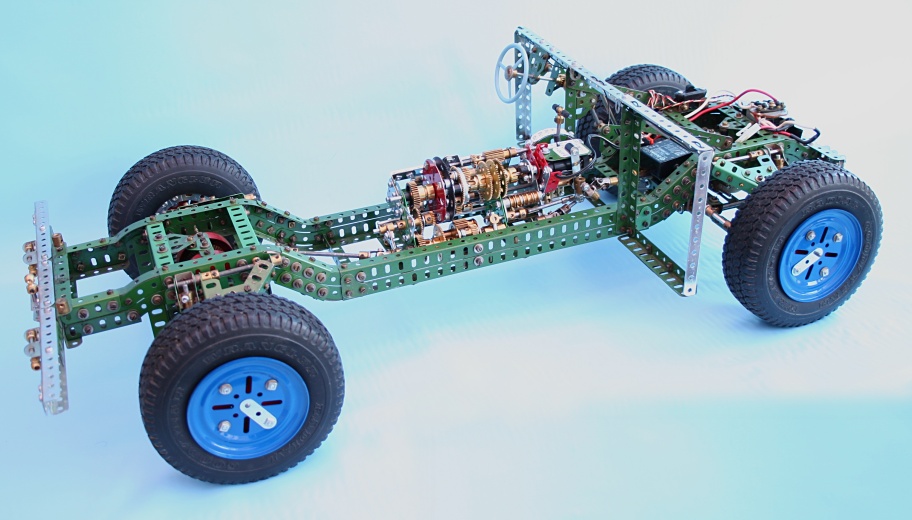

Back in the UK, the gearbox suffered a seizure due to the dreaded keyway axle rods deforming under pressure from the key bolts. The AMG Hummer was equipped with the GM 4L80-E Hydra-Matic 4-speed automatic transmission and thoughts turned to thinking about what to replace the gearbox with? I had no intention of modelling a multi-stage epicyclic gearbox in Meccano, but something led me to look into what automatic transmissions were used in early European cars — it was the Borg Warner series 8 and 35 transmissions. These used an intriguing single-stage epicyclic gear known as a Ravigneaux gearset, which achieved 3-speed and reverse in compact form. This led to another adventure in modelling the Ravigneaux gearbox in Meccano, which was the subject of an article in the September 2006 issue of Constructor Quarterly.

My model of the Ravigneaux transmission featured 3-speeds and reverse, a Hi-Lo range change, a spur gear inter-axle differential and diff-lock. It was fitted into the Hummer chassis as shown in figure 18, in which it performed with great success. The table below shows the prototype Hummer specification and the equivalent calculated values for a 1:6 scale model against the actual model values.

| Specification |

Prototype |

1:6 Scale |

Model |

| Curb weight (turbo-diesel) |

7,050lb |

32.6lb |

32lb |

| Length |

185” |

30.8” |

30½” |

| Width |

86.5” |

14.4” |

14½” |

| Height |

75” |

12.5” |

12½” |

| Track width |

71.6” |

11.9” |

12” |

| Wheelbase |

130” |

21.7” |

21.3” |

| Maximum speed |

80mph |

32.7mph |

0.27mph |

| Wheel diameter |

37” |

6.2” |

6½” |

| Maximum wheel speed |

727rpm |

1,780rpm |

14rpm |

| Acceleration |

0–60mph in 20s |

0–24.5mph in 8.2s |

|

| Acceleration rate |

4.4ft/s2 |

4.4ft/s2 |

|

| Accelerating force (tractive effort neglecting friction) |

963lbf |

4.5lbf |

|

| Wheel torque to accelerate |

1,485lbf. ft |

13.8lbf. in |

|

| Engine power |

170HP |

0.32HP |

0.02HP |

Figure 18 The completed chassis

Sadly the model no longer exists, but it represented a whole new adventure in the research of its features and model-making challenges which produced a great deal of enjoyment along the way.

In 1996 General Motors purchased the Hummer brand name and went on to produce the H2 and H3 models. Production of the H1 (Alpha) model ceased in 2006.

See more photos of this model.