Spring 2018 Newsletter

Spring 2018 Newsletter

Issue 166

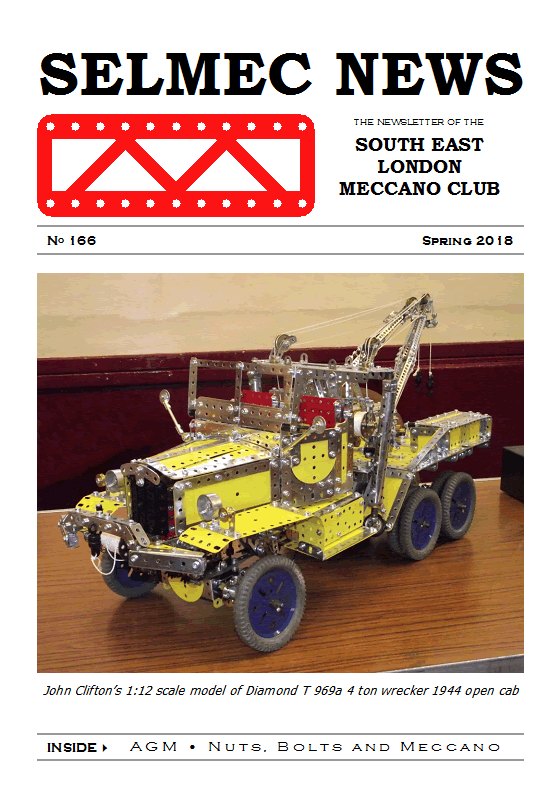

This was one of our informal quarterly meetings where our members showed off their latest Meccano creations.

At around 2:00pm we had a short committee meeting, followed by the Model Tour in which members were invited to give a short talk about their models — in particular their entries for the Secretary’s Challenge!

Written by Richard Marsden

It’s hard to imagine a world without the screw thread, and nuts and bolts. Just about everything in the modern world either contains them, or is extracted, harvested, processed, produced, or transported by something else that does.

It wasn’t always like this; the first woodscrew (and screwdriver) has been traced back to about 1475. Nuts and bolts appeared at about the same time. Bolts were in fact easier to make because the thread did not need to be tapered to a point like the woodscrew. Before this, wooden pegs, nails, and simply roping things together were the order of the day. Strangely, the Archimedes screw for raising water dates from about 260 BC, and by about 60 AD there were wine presses using wooden screw threads, but it seemed to take about 1400 years for someone to think of using the helical thread as a fastener.

It could be that existing methods were adequate, given that threaded parts were notoriously difficult to make. When they did appear, nuts, bolts and screws were time-consuming and expensive to produce. They were either filed and scraped by hand, cut with brute strength by taps and dies (and how did they make these?), or cut on primitive lathes. Threads were relatively shallow and not very strong. Close tolerances were difficult to achieve, so nuts and bolts were usually made as matched pairs. Businesses either made any nuts, bolts and screws that were needed themselves, or bought them from outside in very small quantities, maybe even singly.

It wasn’t until the mid-18th century that automatic thread-cutting machinery began to be developed (the preferred method today is cold-rolling; cutting, milling or grinding is usually reserved for large screws or bolts, extreme accuracy or ‘specials’). Automation would eventually reduce prices by several orders of magnitude, and produce a better result, but this alone was not enough; it was standardisation that really got things moving. Now you could afford to hold a stock of nuts and bolts, and you could buy them anywhere, any time. You could choose an appropriate size for each application, and you knew in advance how big to drill the hole for the bolt.

Bolts L–R: Domed; Coned; Cheese head, Japanned; Cheese head, plated; Small cheese head, steel (not a set-screw); Cheese head, steel; Domed head, plated (from Meccanoids set, c. 1979)

This revolution started with Henry Maudsley. He understood the importance of accuracy and consistency in manufacture. He believed that parts should be made to specified dimensions, rather than being trimmed and filed until they fitted. Most importantly, each dimension should have a specified tolerance, there being no such thing as an exact physical measurement. He devoted much time to making increasingly accurate measuring aids, such as lead screws and engineering flats. He died in 1831, but his pupil Joseph Whitworth carried on the good work and in 1841 established a series of thread standards that we know today as British Standard Whitworth (BSW). Establishing any technical standard is an achievement; establishing the concept and getting everyone, including your competitors, to comply is an even greater one. Standardisation really proved its worth a few years later in the Crimean War, when companies were forced to share work out to meet Government deadlines.

Nuts L–R: Top: Square, brass; Square, steel; Square, steel, chamfered. Bottom: Hex, plated (from Meccanoids set, c. 1979); Hex, steel; Hex, originally brass plated?

But as a wag once said, “Standards are so important you need plenty of them”. No self-respecting plumber would use the same fastenings as an electrical engineer or garage mechanic. There is, after all, plenty of scope for variation, not just the bolt diameter and the thread pitch, but the thread depth, angle and profile, not to mention the shape and size of the bolt head and the nut and the method of driving them. Wikipedia lists dozens of examples. (It quickly ceases to be a joke, however, when similar but subtly different fasteners are mixed, and a joint fails. In 1990 a BA pilot was lucky to survive when his plane’s windscreen blew out in mid-air. It had been fitted with screws one size down from what was specified. They were big enough to take up the thread in the frame, but not securely.)

M4 bolts L–R: Torx; Pozidriv (Westfield Fasteners); Pozidriv (Screwfix)

BSW remained hugely popular in Great Britain for many years, and can still be bought today. When sixty years after its introduction Frank Hornby had to choose a thread size for his new construction toy, it was 5/32” BSW. Remarkably,

as we know, it remains the same today.

Not that there haven’t been variations. A 6BA thread was used in the Motor Car Constructor and some of the Aero Constructor kits. That may have been because the smallest BSW sizes were by now losing out to BA sizes (although 3BA would have been the closest match) or simply because it was smaller. Hornby originally chose a square nut, probably for cheapness, a choice that has also endured, but there was a flirtation with the more conventional hexagonal shape in the 1970s. The latest square nuts are slightly chamfered instead of having sharp edges, a concession to a generation whose hands aren’t hardened by manual work perhaps. The early bolt heads were slightly tapered and domed. The more familiar cheese-head shape was adopted, I believe, about the end of the 1920s. The big change came in 1990 with the hexagonal head replacing the slot. Examining my stock reveals four different shapes of hex head, from slightly chamfered cheese head to domed head, although I can’t be sure if these are all genuine Meccano.

Now, I have a confession to make. A few years ago I added some 6mm-long M4 Pozidriv bolts and M4 nuts to a Screwfix order (they don‘t sell these small bolts any more). The bolt heads have a larger and flatter bearing surface than Meccano bolts, and I could use my socket set tools to tighten the nuts. However, the Pozidriv cross is profiled to force the driver bit to ‘cam out’ unless a very large axial force is applied to the driver. This is deliberate, to avoid over-tightening. In the confines of a Meccano model it can be impossible to exert much force at all, and this can be frustrating. And with different sizes of Pozidriv recess and its similarity to the Phillips head it’s all too easy to use the wrong bit anyway.

I was therefore pleased to see a couple of years ago that another supplier was selling Torx-headed bolts at the same price as their Pozidriv offerings. So I placed an order, and added a couple of thousand thin M4 bolts for good measure. These are only a little thicker than Meccano nuts, 2.1mm versus about 2mm, whereas the ordinary M4 ones are rather bulky at about 3.05mm. You can buy square thin M4 nuts too, but they are so easily mixed up with modern Meccano nuts that I’m not tempted. (Like the hexagonal M4 nuts they are 7mm across flats. Meccano nuts are about 6.5mm.)

Hex bolts L–R: Pan head, heavy chamfer, steel; Pan head, light chamfer, steel; Pan head, light chamfer, japanned

So what do I prefer using? My first Meccano set was a 1954 № 4, with cheese-headed bolts and square nuts. So I always like the look of a model that uses these, whether brass, blackened or silver. It is strangely satisfying to come back to them after using the metric versions. The pre-hexagonal nuts seem to grip the part better than the modern ones (a rougher surface perhaps), so a spanner isn’t always needed. And I still have the Meccano boy’s reflex, moving my left hand quickly away the instant I sense the screwdriver blade slipping from the slot. I bought a box spanner early on. A square-nut driver would have been welcome too, but was probably too expensive for Meccano to produce and wouldn’t have sold well enough. Incidentally, the nuts in my first set were grey in colour and had a tendency to split in half when tightened. I think they all went this way. The exposed surfaces had a granular appearance like cast iron or sintering — the use of a low grade steel maybe.

Nuts with nylon inserts L–R: M4 (on Screwfix 16mm M4 socket-headed bolt); modern Meccano — easily confused!

The Meccano hex bolts can be held on the end of the key when the placement is awkward, which is useful. However — and I think it’s mostly the poor quality of the key — it’s easy to round off the hexagon, so the key spins uselessly or jams in the bolt head. I find it’s better to use a screwdriver with a hexagonal tip. I have also bought some hex-headed M4 bolts (no chance of salvation for me now!), which both look and work better, even if rather taller.

The main advantage of the M4 fasteners is, as I said, that a wider range of hand tools can be used on them. They are fully compatible with Meccano (excluding nuts, bolts, screwed rods and parts with tapped holes, of course), and certainly much better made than all but the most recent Meccano fixings. For the record, the nominal major diameter of the BSW bolt is 3.969mm, the M4 is of course 4mm. The BSW is 32 TPI, the M4 just over 36 TPI. The M4 threads mate easily and closely, and strength is more than adequate; I have never stripped a thread yet. The larger bolt head on M4 means that a washer isn’t needed over a slotted hole, and the slight extra height of the head, about 0.3mm greater, isn’t a problem. One drawback is that 7mm spanners are too thick to tighten lock-nuts. But I don’t really approve of lock-nutting; it implies that a threaded section of a bolt is being used as a rotating bearing, rather than a plain shaft.

I will repeat that I don’t find the Pozidriv head at all easy to use. The Torx head, by contrast, is a dream. The bolt can be held on the bit, not quite as securely as the hex head, but well enough, and the engagement is very positive. There is no tendency to cam out, and the Torx recess holds its shape. I have had no ‘rounding’ issues as I did with the Meccano hex heads.

M4 Torx bolt with T20 driver

If you like your models to look like Meccano, and I fully understand and appreciate this, then all this talk of metric parts will have left you cold. But if you like experimenting, I would recommend you try the Torx system. It is a good engineering solution and I’d like to think Frank Hornby would have chosen it if it had been available in 1901.

There is far more to the subject than I’ve covered here, but I hope you found this article riveting. Actually, that’s a method of fastening I haven’t mentioned at all! Now I think of it, 4mm is a standard pop rivet size, and I rarely take my models apart, so with the next one maybe I could…

Inevitable postscript: A screw fixes into a threaded hole in at least one of the items it is securing. A bolt passes through plain holes and is secured at the back by a nut. This simple definition has sufficed for Meccano (set-screws and nuts with bolts), and makes sense to me!

Legal postscript: Hex heads are sometimes referred to as Allen heads. This name is still registered to a specific manufacturer, who understandably does not approve of its use except for its own products.