June 2010 Newsletter

June 2010 Newsletter

Issue 135

This was one of our informal quarterly meetings where our members showed off their latest Meccano creations.

At around 2:00pm we had a short committee meeting, followed by the Model Tour in which members were invited to give a short talk about their models — in particular their entries for the Secretary’s Challenge!

Report written by Peter Clay

On 1st May 2010 members of SELMEC put on an exhibition at the National Maritime Museum, undoubtedly the most prestigious venue this club has attended. This was at the invitation of the museum’s Public Programmes Co-ordinator Sarah Hicks, and tied in with their 1930s themed festival celebrating the opening of their new Toy Boats exhibition.

I arrived to find members already busy setting up, with Frank Paine arranging one of his superb montages. We exhibited in the entrance hall of the museum by the bookshop in an area professionally roped off for us. An enormous ship’s propeller was rotating above (directly over my head!) It was possible to see our entire exhibition from the gallery above.

A view of our exhibition from the gallery

The museum seems to have been considerably expanded and refurbished since I last visited and it must be the first time I have not been able to see the observatory and clocks. The new Toy Boats exhibition included Meccano, Hornby and Dinky items, together with three working hands-on examples of model boat propulsion, two of which were out of action! How unlike our models!

However — on to what you really want to know: Our models, in order from the front window inwards, were as follows:

Chris Warrell had his HR1 London tramcar. This model, three feet long, ran throughout the exhibition along ten feet of track. I could see that for many young visitors this model provided the real WOW! factor. Adults, as well as museum staff, were as fascinated — and this must be said of the whole exhibition. Chris also brought three ship models in blue and gold, from outfits 3 and 4 of the time — a submarine, a battle cruiser and river gun boat.

Chris Warrell boring a poor woman to death! (Photo: NMM)

Adrian Ashford was unable to attend since he was in Welling running his Hornby Trains exhibition. He did however also show a ship — the liner ‘Empress of Britain’, which was beautifully made in a striking, predominantly white colour scheme.

Chris Fry showed Bernard Perier’s Triumph open sports car sporting spoked wheels and well detailed. Also from that Gallic wizard he had a miniature (O gauge?) railway breakdown crane, hand operated but with all movements working. From the same source was an open MG sports car. He also had a small car with rotating spoked wheels mounted on a display stand. Not content with all this he showed the SML steam shovel, with an improved gear box and a dummy steam plant powered by an electric motor: another model, running throughout the day, to the fascination of spectators. Visitors were also intrigued by his ‘hands-on’ inertial unidirectional mechanism.

A family are fascinated by Chris Fry’s models (Photo: NMM)

Tim Surtell always does us proud on the publicity front. He had a continuously running laptop display of 1930s models, Meccano Magazine covers etc. including SELMEC models. This was also visible on a large screen behind the club’s display. I think the museum downloaded it for their own use. Tim also designed the new posters for our October exhibition which were, of course, on display.

Peter Clay had a 1930s touring car and caravan from the 1935 Meccano Magazine series ‘In search of new models’, built from the photographs and description (as no detailed instructions were given). It looked good in a yellow, silver and black colour scheme with plenty of brassware for the lights, horn, etc. The tapering chassis and bodywork made it difficult to build and it was not possible to motorise it. A foundry hand-operated portable crane from 1930s manual proved popular with children, who liked winding up the hook until it was jammed at the top! Turning a crank does not come naturally to the youth of today. My Goliath Pioneer 3-wheeled German light car, fitted with an electric motor, had a tight turning circle enabling it to be run around on the table top, probably at scale speed as the original had a 1-cylinder 2-stroke engine! Also shown were a small sports car and ‘Dad’s Army’ van.

Brian Elvidge brought a level-luffing crane, worked by hand, from an Meccano Magazine model which appeared to have narrow strip bracing. Children enjoyed seeing this work, as well as Brian’s clockwork car which ran effortlessly around the floor. The gas engine from the № 6 Meccano manual looked impressive in operation and was powered by an E20 motor which really does look like an electric motor. He also had an Empire State Building from the new sets in Liverpool colours.

Brian Elvidge amuses one family (Photo: NMM)

Frank Paine as always put on a substantial display of models, sets, Meccano Magazines and showcards of period models and prototypes. His № 10 set ‘Schools’ class locomotive took pride of place, with its wheels and motion work turning at the press of a button, like his SML1 motor chassis. These models impress spectators seeing them for the first time but never lose their appeal. I could see young people fascinated when they could work a gear lever and actually see what happens — just what Frank Hornby intended! Frank also had a biplane from the Aero constructor series, a ‘Royal Sovereign’ battleship and 1931 4A outfit nestling temptingly in its box.

Frank Paine with his locomotive (Photo: NMM)

Brian Leach brought his motorised ‘Ames Window’ illusion which kept spectators’ attention. I must confess I found myself frequently mesmerised by it — it never loses its effect. Was it rotating, reversing or changing its shape? Despite Brian’s instructions to view it from a distance, people kept peering from a few inches away — out of fascination no doubt.

Douglas Windibank had an appealing exhibition of period style models. A biplane, crane and lorry crane all came from the Marks and Spencer ‘vintage’ sets which, although wildly inaccurate historically, gave a good impression of early (pre flexible plate) 1930s models. He also had a steam wagon from set 5 plus a Magic motor which had a good turn of speed.

Douglas Windibank chats to visitors (Photo: NMM)

To sum up: The exhibition went well and seemed to be well attended. It appealed to children, parents and grandparents alike many of whom, given the nature of the venue which is a listed tourist attraction, came from abroad. As at Kew Bridge Steam Museum, museum venues have a lot to recommend them. The reaction of the National Maritime Museum staff to our display was, as I said, very encouraging and appreciative and it is to be hoped this is not the last time our hobby is represented there.

Even the weather co-operated, not being fine enough to draw spectators to the coast, etc. Unfortunately it let us down towards the end, our loading and leaving being done under torrential rain — a small price to pay for a worthwhile day.

Another view of our exhibition

Written by Greg Clarke

Brief History

‘Big Hog’ at work

The 3850B nicknamed “Big Hog” was Bucyrus’s largest shovel type and when it was first commissioned in 1962 it was the heaviest land machine ever built. It weighed 9000 tons and had a bucket which could dig out 160 tons of rock in a single bite! It soon lost the heaviest accolade however to its sister machine in 1964 then ultimately to the mighty Captain shovel built by Marion in 1965 which exceeded 15,000 tons! These massive machines were used to remove overburden at surface coal mines in the Midwest and central parts of the United States. The hog was retired and buried in its own pit in 1984 when the mine was shutdown, and its sister machine went the same way in 1993.

The Model

I’ve been fascinated in large mining equipment since I picked up a book on the subject at a steam rally in the 80s, so it was natural that I would have a go at one in Meccano at some time. I read with much interest about Guys Captain shovel that won the Issigonis shield eight years ago so I didn’t want to copy it and needed to pick another machine. Big Hog was a natural choice as it used several quite different engineering features to the larger Marion built machine, and would present some interesting challenges.

Watch our video of this model

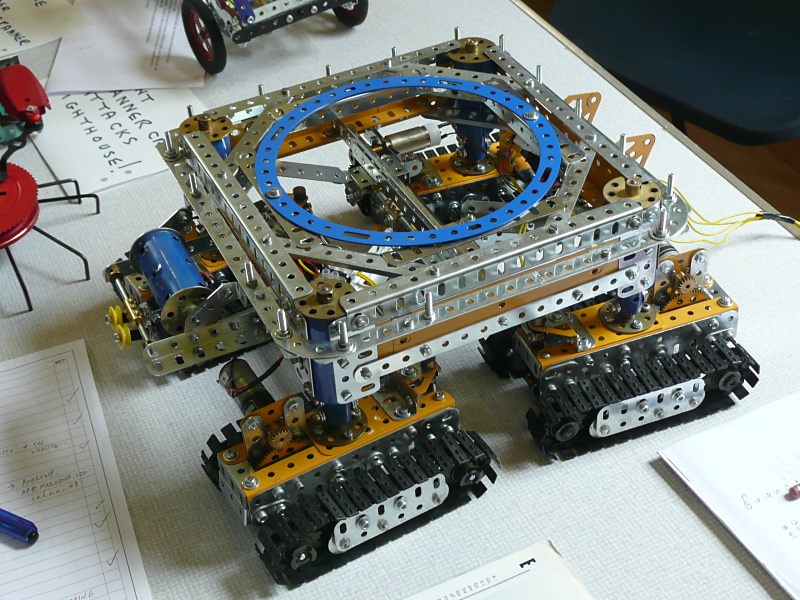

Crawler Sets

The machine is propelled by four sets of double crawler tracks mounted under replica cylinders at each corner of the lower works. Each one is built up using 5½” angle girders and flat girders with a 1½” square plate and wheel flange mounted on the top to take the weight of the machine. Each crawler would need to be independently driven with small but powerful motors. For this job I purchased four Swiss made 350:1 geared motors with 3mm drive shafts and sent them up to Stuart Borril to get special 19-tooth pinions and 1½” square plates pre-drilled for mounting. Each 19-tooth pinion meshes with a 57-tooth spur gear which then transmits the drive via small sprocket and chain down to the plastic caterpillar track sprockets. The plastic sprockets have been drilled to accept collars inside as the torque and model weight (17kg) would soon strip them out. At the opposite end of each crawler set there is a single HD compression spring to act as a tensioner and help prevent the tracks coming off the sprockets as they like to do. The crawlers attach to the lower works by 5” rods journalled through 3½” sleeves and 2½” cylinders which simulate the massive hydraulic cylinders used on the original.

Lower Works

This is the name given to the box like structure which the crawler sets and slewing support ring is mounted to. Again this had to be very beefy so I used 7½” and 5½” angle girders top and bottom of each side plate with four wheel cylinders to act as the top journals for the support cylinders. To support the slew gear there is a single 7½” circular strip bolted across the top of the angle girders. Upon this are eight threaded collars and four rod sockets. At one end I built a mock up of the giant electric cable reel complete with cable guide. At the other I made up a small junction box hidden behind a flexible plate on a hinge to make access easy when the top and bottom halves have to be separated for transport etc.

Lower works and crawler sets

Steering

The steering is performed by a 100:1 geared motor which drives a worm meshing to a 19-tooth pinion. This is attached to a special extended length rod socket threaded to 6mm which screws onto a threaded shaft. An identical rod socket is fitted to the opposite end and these both journal into a 62b double arm crank which provides a strong thrust bearing to counter the load when the shovel steers. A special M6 threaded coupling runs up and down the shaft to which is attached two sets of seven hole narrow strips sandwiched three thick. These again via couplings attach to 7” rods which act as the tie rods with swivel bearings at each end. Finally the swivel bearings with shafts mounted vertically pivot at the inner end of each crawler set. This all works quite smoothly and the despite the weight the motor runs effortlessly. The weakest part is occasionally the couplings slip on the 7” rod causing uneven steering angle and have to be re-aligned.

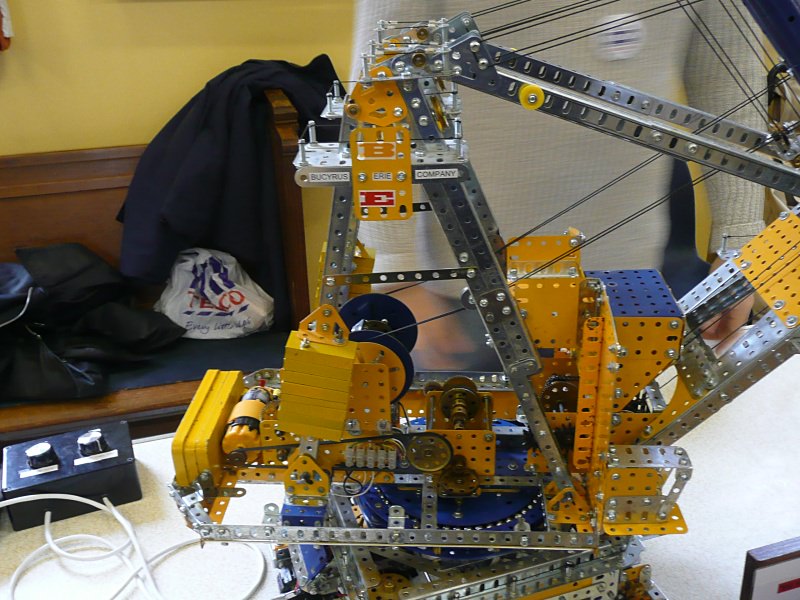

Upper Works

This is the name given to the machinery house and the support for the boom and A frame. It is constructed very simply from 12½” girders mounted onto a series of 5½” x 2½” hole plates attached to the 6” circular plate of the slew gear. I decided to build all of the slew gear to the upper works including the roller bearing assembly and a cage which supports the 3½” ring gear. To increase the teeth contact area a 3½” gear wheel is sandwiched to a 3½” gear ring. At first a single 19-tooth pinion was used for meshing to the main ring but it soon became obvious this would not be man enough so a major refit of the machinery deck was required. A PDU motor set at 6:1 to save the expensive gearbox uses a large belt drive to a 1½” pulley. This in turn drives through a friction clutch and various reduction gears. Finally drive is changed vertically via contrates to the two shafts which are attached to the 19-tooth slew drive gears. This all works fairly smoothly at a slewing rate of about 3 rpm. The clutch provides some protection if the machine is turned without using the motor. The crowd mechanism is driven by an MO motor and 19:1 reduction gearbox mounted in the vertical. This in turn using a 171 coupling and two shafts then performs three sets of reduction before the final chain drive. The drum is formed from two 6-hole flange wheels connected by 4” rods. One cord only performs all the crowd movement.

Upper works

A Frame and Hoist

The A frame is made from various angle and flat girders and features two maintenance decks complete with hand-railing. You will note from the photos several miscellaneous ½” and ¾" pulleys mounted to the top cross brace and each A frame between the maintenance decks. These pulleys don’t appear to be performing any function, but they match the prototype and after investigation I found out that they were used during the building of the machine to raise the 500 ton boom section using the shovels’ own hoist ropes. After the machine was complete all this redundant equipment was left in place. Two sets of angle girders are used as the main boom bracing which is attached to the top of the A frame and pins to four trunnions attached about a third of the way up the boom.

The hoist machinery was rebuilt at the same time as the slew gear as I was not happy with the original. The problem was that in order to duplicate the prototype’s twin rope arrangement for lifting the shovel’s stick and bucket, any unequal paying in or out of the rope drum would result in the cords going slack on one side and looking unsightly. Clearly a differential was required so that’s what I did. The hoist is driven by an MO motor gearbox combination after several spur gear reductions. Drive to the differential is via a chain drive arrangement. Tension adjustment for this drive is taken up via 96a 14-tooth sprocket which has come loose from its boss. This makes a perfect idler sprocket from an otherwise useless part!

Two sets of boiler ends and large flange wheels form the two hoist drums. The two cords for the hoist both start and end at the drum which is unusual but matches the prototype. There is no mechanical advantage in multi-reeveing with this design, so I can only assume the designers used the double breaking strength advantage of two cords. The arrangement is simple with each cord ran over the boom head 2” pulley, down to the dipper 2” pulley then passing each side of a 1” pulley that swings freely from the top of the boom head.

Boom

The boom is quite flat but very wide compared to crane-style booms. The lower part uses various yellow and zinc parts that appear almost solid in construction with the upper made up from a series of chevron style cross bracing. The boom head is suitably busy and the whole affair is adorned with maintenance platforms complete with hand railing. Four cords on each side run from the A frame to the boom head to act as upper boom support ropes, with two additional cords per side running vertically down to the mid-boom level. One visitor at SELMEC likened it to the rigging on a ship, but I have only modelled half of what is on the prototype!

Saddleblock

The saddleblock is the name given to the giant bearing assembly that supports the stick and allows it travel smoothly back and forth when the machine is digging. This motion is called ‘crowd’, the drive mechanism of which I covered earlier in this article. The saddle block frame is a simple box arrangement of angle girders pivoting on the centre to allow the whole assembly to pitch. As the stick is formed using a series of sleeves bolted together, a smooth bearing was required that also allowed the stick to ‘yaw’ slightly. This was a feature of all Bucyrus Erie rope crowd shovels as they soon discovered that when the shovel hit a hard rock face the side shock would be absorbed by the boom and pivot mechanism causing a lot of damage. To achieve this I came up with the idea of using 8½” tyres fitted to plastic collars to give a front and back four-point bearing surface. These run freely on 1½” rods journalled into 133a trunnions. The spring tension which allows the ‘yaw’ movement is created by two sets of two compression springs pushing the trunnions out to keep constant tension on the side of the stick. The arrangement worked first time and I was suitably pleased with the effect.

Stick and Dipper

As mentioned above, the stick is made from the longest sleeves that Dave Taylor can offer bolted together from the inside using strips to link them. At each end a set of white plastic 1” pulleys act as crowd pulleys. The stick was hollow on the prototype; 7’ in diameter, 3” thick, and 140’ long. It had to be reinforced with another 3” of steel soon after entry into service due to stress cracks. The dipper includes the bucket which is fixed to the stick and the hoist pulley assembly. At the time of writing this article I had not bothered to model the hinge mechanism of the bucket but I may do so later in the year. It’s construction is clear from the photo. The hoist pulley is formed of two 2” pulleys which are free to pivot in two planes independent of each other. This makes reeving of the cord interesting, especially with a differential always trying to take up the slack!

Conclusion

The model has taken about a year to complete with an estimated 200 hours. It has been enjoyable with several challenges overcome. I plan to keep it for the summer season of exhibitions before it becomes something else! For me the building is the pleasure and once complete I am itching to start the next one!

The Bucyrus Erie 3850 Giant Stripping Shovel model